In this post, I describe my solution for the Jenga problem from The Riddler. But first, the riddle:

In the game of Jenga, you build a tower and then remove its blocks, one at a time, until the tower collapses. But in Riddler Jenga, you start with one block and then place more blocks on top of it, one at a time.

All the blocks have the same alignment (e.g., east-west). Importantly, whenever you place a block, its center is picked randomly along the block directly beneath it.

On average, how many blocks must you place so that your tower collapses — that is, until at least one block falls off?

For additional explanation, visit Riddler’s official page.

Why does the tower collapse?

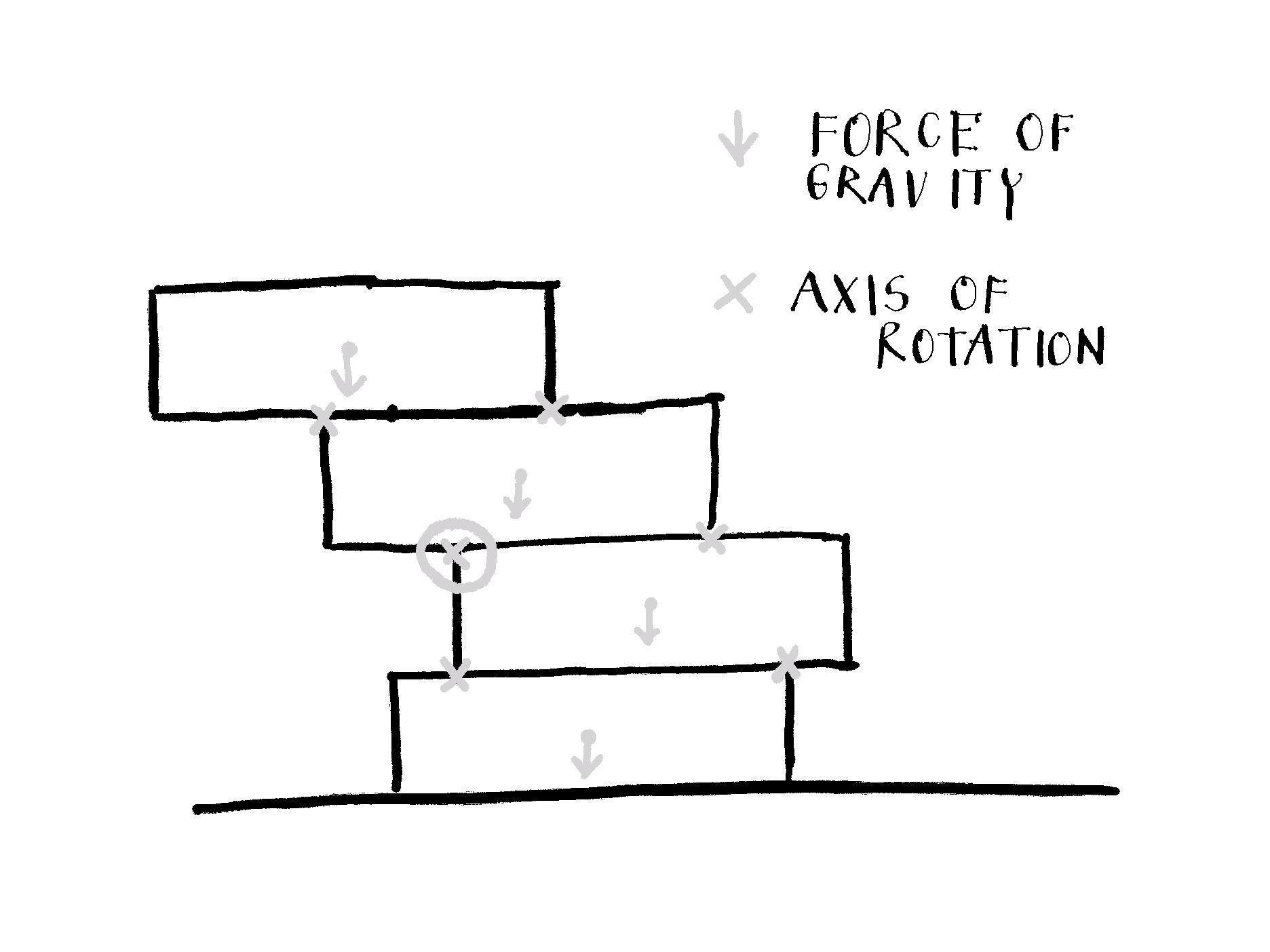

Let’s say we have the Jenga tower (as on the sketch) and want to calculate whether it’s stable.

Physics says that the tower is stable when sum of forces and torques acting on it equals zero: \[ \sum F = 0 \] \[ \sum \tau = 0 \]

The tower collapses when one of these equations is not fulfilled. Forces are not problematic: only forces of gravity act on the blocks’ centers (you can see them on the sketch). But they get neutralized by the opposite force of the blocks below and table.

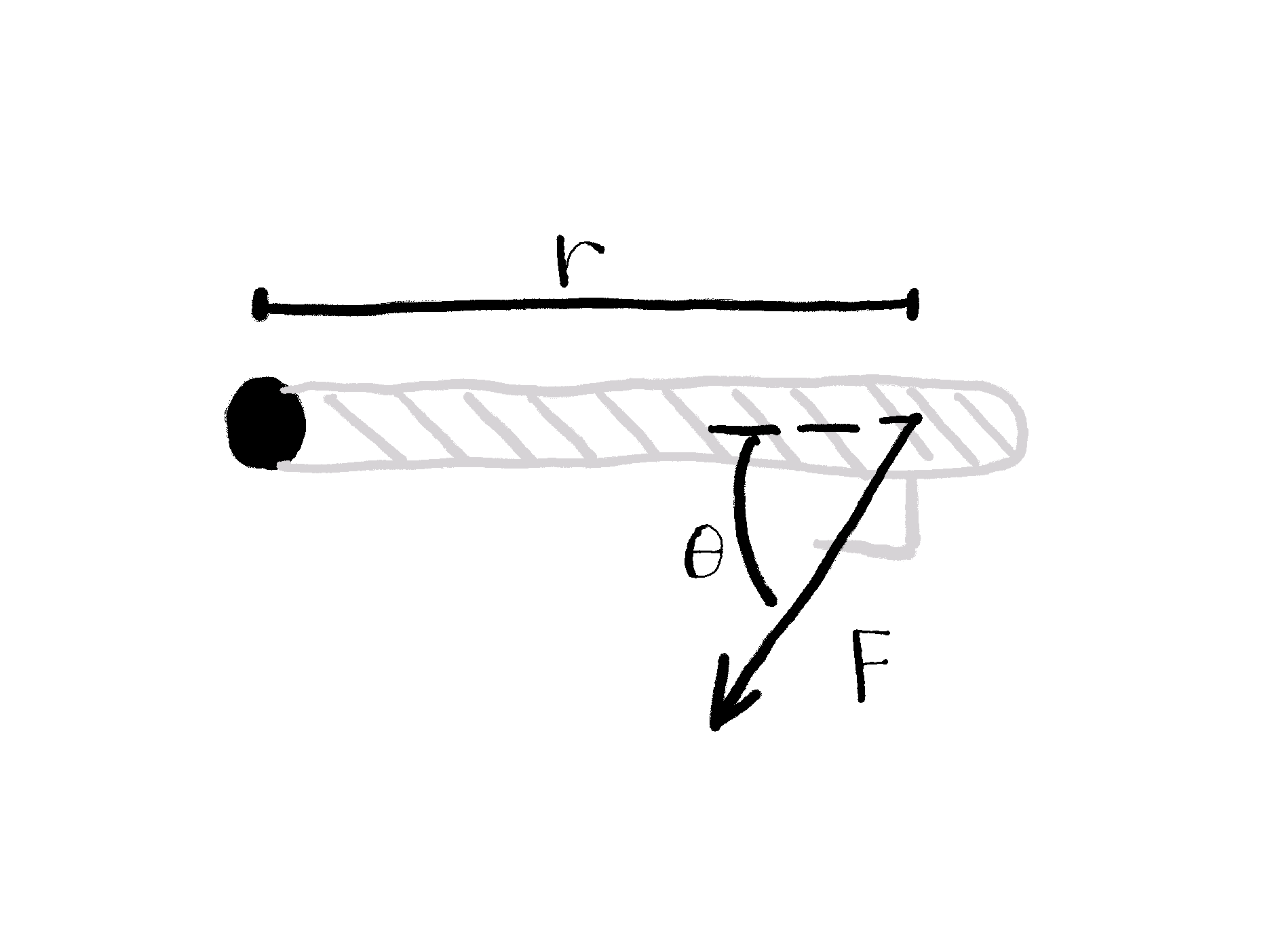

The collapsing Jenga tower rotates, not drops. The problem is imbalanced torque. Potential axes of rotations are edges of the blocks.1 They are marked with \(\times\) on the sketch. The sum of torques has to be 0 for each of these axes. Torque is defined as: \[ \tau = F \cdot r \cdot sin\theta \] where \(\tau\) is torque, \(r\) moment arm, \(F\) applied force, and \(\theta\) the angle between the force vector and the lever arm vector.2

To better understand torque, look at the sketch above. It represents the door from above. Someone wants to open them by applying force at the door handle. Torque is applied on the door hinges and can be calculated by the equation above.

In the same way we can calculate (sum of) torques on all blocks’ edges. The situation is even simpler: we only care that the gravity center of any block (or multiple blocks together) is on the lateral side (farther from the tower’s center) compared to the edge of some brick (potential axis of rotation). This torque can’t be compensated (there’s nothing on the other side, just air resistance) so the tower collapses.

On the Jenga tower sketch, circled \(\bigotimes\) marks the axis around which the tower rotates when collapses. The center of gravity of the top 2 blocks is more to the left compared to the axis of rotation.

Enough theory, let’s code

Let’s assume each block has uniformly distributed mass and is 1 unit long. Each time we add a block its center is picked randomly along the block beneath it. The calc_next_block_center function does that.

calc_next_block_center <- function(previous_block_center) {

previous_block_center + runif(n = 1, min = -0.5, max = 0.5)

}

The are_block_above_balanced function calculates whether the blocks above some block are balanced. The condition for that is that position of their combined gravity forces is less than half a brick away from the center of the brick beneath them.

When we place a new block we have to check are_blocks_above_balanced for every block (excluding the one we placed) and the blocks above it. The get_all_possible_subtowers function makes this easier. It returns all possible subtowers: for example, if the tower has 5 blocks (block 1 at the bottom and block 5 at the top). The function returns the subtowers [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], [2, 3, 4, 5], [3, 4, 5], and [4, 5]. The lowest block in the subtower is then passed as the block_center and others as block_centers_above to the function are_blocks_above_balanced.

With get_tower_top_level we are measuring how many blocks the tower consists of when collapses.

We always start building the tower with a block that has a center at position 0. Then we place the next block using calc_next_block_center. By concatenating block_center and next_block_center we get a new, taller tower. Possible subtowers, created with get_all_possible_subtowers, are then split by the bottom block and the blocks above and passed to are_blocks_above_balanced. When any of the are_blocks_above_balanced returns false, while loop breaks and all blocks in the collapsed tower are counted.

get_tower_top_level <- function(...) {

block_centers <- c(0)

is_tower_balanced <- TRUE

while(is_tower_balanced) {

next_block_center <- calc_next_block_center(tail(block_centers, n = 1))

block_centers <- c(block_centers, next_block_center)

subtowers <- get_all_possible_subtowers(block_centers)

is_tower_balanced <- all(purrr::map(

subtowers,

~are_blocks_above_balanced(.[1], .[-1])

))

}

length(block_centers)

}

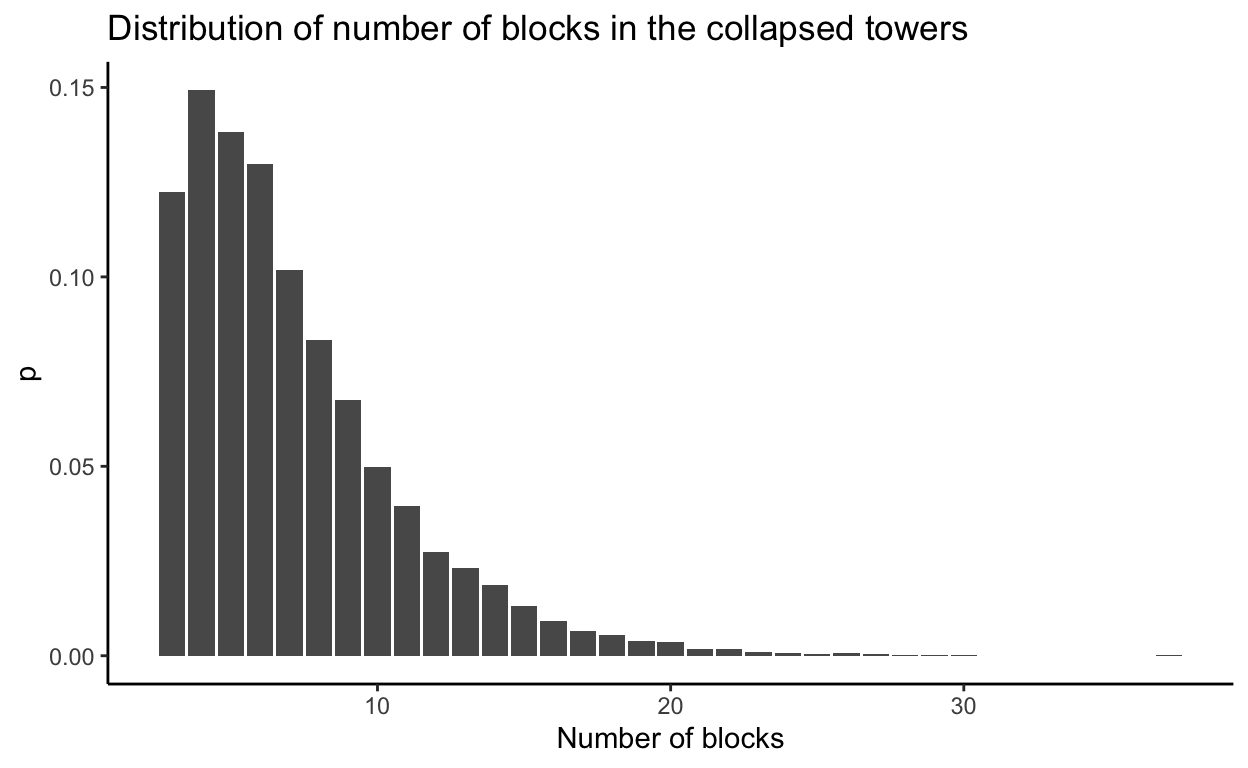

To get the approximation for the average number of bricks in the collapsing tower, we simulate building ten thousand towers.

We can plot the distribution:

Now, let me rest my brain (but not my nerves) by playing Jenga.